Arsenic: a domestic poison

12 Oct 2018

Susan Isaac

The dangers of arsenic were recognised at the time. Copious pamphlets and articles in the scientific press were published about the subject, some of which are kept in the RCS Tracts collection. Pamphlets were the social media of their day, used to share information, ideas and opinions about everything. Today they are fascinating to read, as they contain so much interesting social history.

Henry Carr collected evidence from a number of medical and chemical authorities to write ‘Our Domestic Poisons or the poison effects of certain dyes & colours used in domestic fabrics’ in 1879. The following year he read the sequel, ‘Poisons in Domestic Fabrics in relation to trade and art’, at the Society of Arts. His papers are comprehensive in their coverage of the issues, both from the point of view of the public and of the manufacturers. He examined the freedom of action manufacturers had, laid out the Parliamentary actions required and covered the health issues for the public. He told the stories of harm caused: the sad story of a child in Peckham who died after sucking on a piece of arsenical wallpaper, the person who wore stockings that caused serious irritation on her legs or the bronze green gloves that made the hands swell. Robert Brudenell Carter FRCS, reported that he had reason to believe that two of his children died from an arsenical wallpaper in their nursery. A case from Birmingham tells of a couple and their parrot, who all became ill within a week from the wallpaper, all of whom recovered after the paper was removed. Less lucky was the wife of Dr W, a London surgeon who brought Scheele’s green wallpaper: six months later she died, apparently from the effects of arsenical poisoning. Even something as glamorous as a ball gown could be lead to oozing sores, especially when combined with artificial flowers.

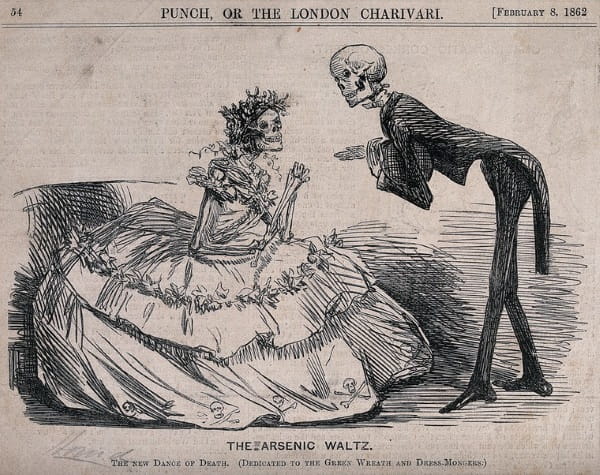

‘Two skeletons dressed as lady and gentleman.’ Etching, 1862. From Punch, or the London Charivari. From the Wellcome Collection, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

Jabez Hogg, a London Surgeon, was one of experts who contributed to Carr’s work but he also published papers on the subject himself. In his 1879 article ‘Arsenic and arsenical domestic poisoning’ he describes arsenic as “a poison in health, and a remedy in disease”. He gives us an overview of the medicinal uses of arsenic, in addition to the risks and symptoms of accidental poisoning from the domestic environment. To illustrate his argument, he tells us about a Member of Parliament who suffered for months from a painful eruption of the feet. His symptoms were so severe, he was confined to home and couch. Eventually the cause of his illness was traced to his fashionable green socks. He recovered quickly once he had abandoned them. Sadly, Hogg relates that several Californian miners died from wearing boots lined with bright green flannel. Hogg writes about people made ill by their wallpaper, Venetian blinds, gloves and chintz curtains. One lady suffers a painful skin disease from constantly carrying a yellow purse in her hand, while another has a troublesome eruption of the skin, caused by the artificial flowers she wears in her bonnet. His later 1885 article, ‘Arsenical poisoning by wall-papers and other manufactured articles’ is a comprehensive overview of the legal situation on the use of arsenic in manufacturing and food production across Europe. Again there are descriptions of harm caused by domestic products.

It wasn’t just consumers who suffered, the workers who produced the goods were also affected. Both Carr and Hogg have examples taken from the different trades affected, from workmen stripping wallpaper who have diarrhoea and other stomach upsets to girls employed to make artificial flowers suffering eruptions, painful cracking of the skin on their fingers and flexures of the arms. From one factory employing a hundred girls, twenty six presented other symptoms of chronic poisoning, one died after months of suffering from ulceration and only four appeared to be symptom-free. A girl working in a draper’s shop selling artificial flowers had to leave her job, as just showing them to customers made her ill.

Eventually campaigns making information accessible to the public led to demands for safer products which along with legislation led to the manufacturers producing arsenic-free products. This benefited both the workers and the consumers. In addition, fashion moved on, the vibrant green lost its caché and the home became a little bit safer.

The National Library of Medicine has digitized Shadows from the walls of death: facts and inferences prefacing a book of specimens of arsenical wall papers, compiled in 1874 by Dr Robert C Kedzie to raise awareness of toxic pigments used by manufactures.

Susan Isaac, Information Services Manager

Add your comments to the site using Disqus.