Medical fiction for popular readers: The Stark Munro Letters (1895)

16 Dec 2016

Alison Moulds

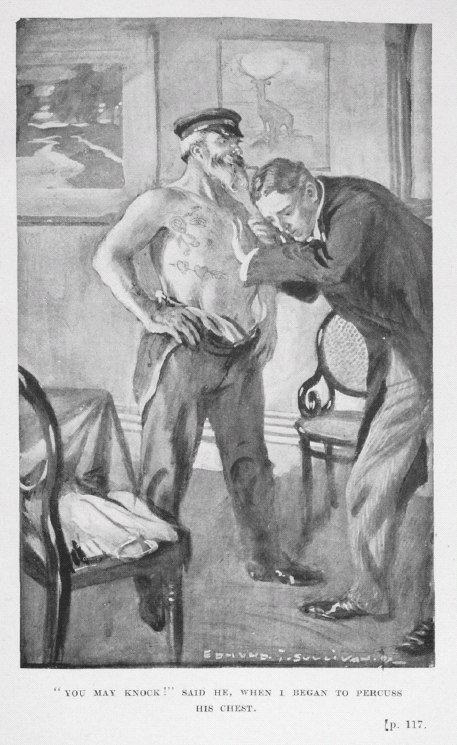

The Royal College of Surgeons’ library has a beautiful edition of the novella, released as part of the Daily Mail’s “sixpenny novels” series in 1907, with illustrations by Edmund J. Sullivan. One of my favourites shows the earnest protagonist, in his respectable frock-coat, percussing a patient – the perpetual drunkard Captain Whitehall – who bares a chestful of tattoos and wears a sailor’s cap atop his head. This image neatly captures the tone of the narrative, which combines playful comedy with sympathetic realism, as well as pathos.

This edition also includes an original wrapper of advertisements, a fascinating insight into early twentieth-century consumer culture. Given the story’s subject matter, it is interesting to note the profusion of household medical products advertised, from Dr J. Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne (billed as a remedy for coughs and colds, as well as consumption, cholera and spasms) to Southalls’ Sanitary Towels, which claimed that “every lady should know” they are a “comfort, convenience […] and an absolute necessity to health”.

The domestic nature of the adverts suggests the publishers anticipated a popular audience for the book, including many women. Yet the story had quickly come to the attention of the medical community as well. Upon its publication in 1895, it was reviewed by the Medical Press and Circular, a long-running weekly (the back issues of which can be found in the RCS’s collection). The journal commends the novel to its readers, suggesting that it “cannot fail to prove of value both to practitioners and students” and even that it resembles an “Introductory Lecture”. The reviewer implies it will serve an instructive purpose, presumably because of its realistic portrayal of the difficulties faced by young practitioners at this time.

The reviewer was not interested solely in the book’s educational function, however. He also designates it “full of fun” and praises the character of Cullingworth as “magnetic, unscrupulous, interesting and many-sided”. The doctor’s unorthodox, even abusive, behaviour towards patients is accepted as humorous, rather than a slur on professional conduct. The review closes by arguing that, as the book “is sure to be in the hands of every patient we cannot do better than advise every medical man to study it with care”. Ultimately, its likely popularity with the public is seen to render it indispensable reading for the medical man.

In the Victorian period, it was not unusual for professional journals to engage with literature by or about medical practitioners. In 1888, the Lancet featured a lengthy article on “The Doctor in Fiction”. It suggested that, since fiction “to no inconsiderable extent moulds, current thought and opinion”, it was not “a matter of indifference” that “professional methods, aims, and work should be honestly depicted, and not maliciously caricatured”. Medical commentators clearly saw the value of engaging with what their patients and the public might be reading. They did not simply wish to see affirmative portraits of practitioners – some emphasised the entertainment value of fiction – but many felt writers had some responsibility to offer faithful depictions of medical life and practice.

Alison Moulds is a DPhil English Literature student at the University of Oxford working on the Constructing Scientific Communities project in partnership with the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Bibliography

Conan Doyle, Arthur, The Stark Munro Letters (London: Amalgamated Press, 1907).

“Literature: The Stark-Monro [sic] Letters”, Medical Press and Circular, 16 October 1895, p. 404.

“The Doctor in Fiction”, Lancet, 7 April 1888, pp. 685-6.