The restoration of a lost nose by operation: exemplified in a series of cases – John Hamilton (1809-1875)

08 Nov 2019

Susan Isaac

John Hamilton was a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and the visiting surgeon to the Richmond Hospital in Dublin between 1844 and 1875. During this period, he carried out a series of Indian rhinoplasties and published his results in 1864 as an essay, The Restoration of a lost nose by operation: exemplified in a series of cases. The essay is illustrated with wood engravings made from photographs taken before and after treatment. It is obvious from this essay, that Hamilton was interested in advances in plastic surgery and that he both read and contributed to the medical literature of the time. His essay references and comments on the work of contemporary surgeons such as Robert Liston, James Syme and Sir William Fergusson.

Hamilton used the Indian method, in which a flap of skin was taken from the forehead. It had been described in Joseph Carpue’s 1816 An account of two successful operations for restoring a lost nose from the integuments of the forehead, in the cases of two officers of his majesty's army. A flap of skin from the forehead was created, leaving one end connected to the forehead, and the free end of the skin flap would then be swung over to the nose, without completely severing the connection to the body. Maintaining the physical connection ensured that blood was supplied to the skin, increasing the chances of the graft being accepted by the body.

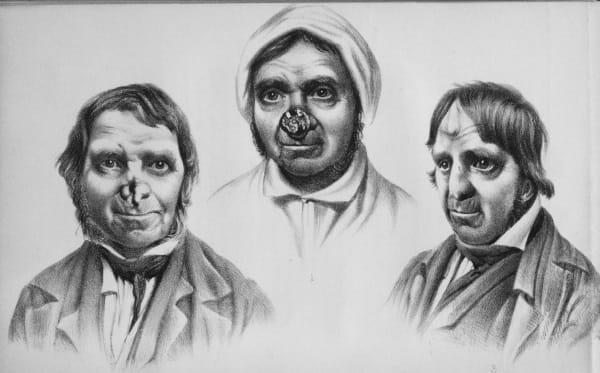

The popular impression at the time was that syphilis was the most common reason for the mutilation of the nose and indeed this was the cause for one of the patients Hamilton successfully operated on. However, in Victorian Ireland, the majority of cases were caused by lupus, which was common among the ‘scrofulous’ poor. Lupus vulgaris is a cutaneous form of tuberculosis, named for the common symptom of severe loss of skin and surface tissue. The patient could be significantly disfigured and faced additional stigmatisation on account of the facial disfigurements’ similarity to syphilitic ulceration.

Before any surgery was carried out, treatments were given to clear the destructive ulceration, using different caustics depending on the individual patient. Hamilton describes ten cases in detail, explaining his methods and the outcomes.

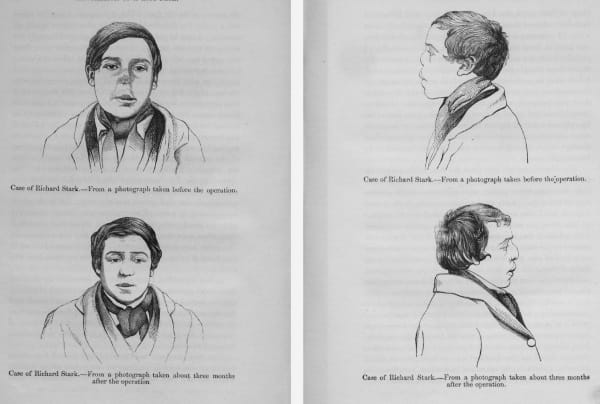

Richard Stark was a 20 year old labourer who had lost half of his nose from lupus, which also affected his breathing. The disease had started eight years earlier, slowing eating away his nose over five years. He had a small ulcer by his mouth and this was treated for six weeks with a course of hydriodate of potash and sarsaparilla, before operating on 30 September 1857. Hamilton explains the steps he took to cut a flap of skin from the forehead and how the new nose was formed. Chloroform was used as the anaesthetic, which can make the patient sick and Stark did vomit as he came round. Four days after the operation, he was feverish but the skin graft had taken and everything was looking good. Eight weeks later, Hamilton reports that the nose is ‘getting quite natural in appearance, as well as becoming firmer and scarcely distinguishable in colour from the neighbouring parts’. A second operation was now carried out to create a septum and a few days later, the final stage of the operation was carried out to separate the flap of skin from the forehead.

Mary Neil was a ‘stout young woman’ aged 18 when she was admitted with lupus, which had destroyed her nose. She had a ‘belt of deep scurfy redness across the bridge of the nose, so common in these cases, it extends to the cheeks and terminates in an ulcerated margin’. The ulceration was treated but it was some months before Hamilton was able to operate, on 5 December 1860. On the third day, he reports everything had gone well although Mary had occasionally been slightly hysterical. He says ‘in no case had I less trouble than this one’. On 28 December, only three weeks after the operation, the nose is described as looking very natural and Mary remarks that ‘she saw that day what she had not seen for ten years, the shadow of her nose on the wall’.

The final case Hamilton describes is that of Thomas Sherrigan, who was 58 years old and admitted with a cancerous ulcer on the tip of his nose. Two years earlier, a small, black wart had appeared on his nose, which grew and became ulcerated. This had been removed and healed, but a second large ulcer had appeared and he’d returned to the hospital. After examining the case, it was obvious the disease was malignant and the decision was taken to remove the nose to preserve Sherrigan’s life. On 8 February 1860, the operation was carried out. It was difficult as when the chloroform was administered, Sherrigan’s pulse became alarmingly weak and it had to be discontinued. The operation was carried out with the patient only semi-conscious. On 20 February he is reported as going on favourably. The left side of the nose looked good but the right was still open. Three months elapsed before Hamilton operated again to restore the nose completely after waiting to see if the cancer returned. On 14 May, Sherrigan left the hospital well. After the harvest work was over, he returned in December, not on account of anything wrong with the nose, but because he had developed a flat, red tumour on his jaw. Despite treatment, his condition became worse and when he left the hospital, Hamilton thought he wasn’t far ‘from a fatal termination of his case’. He also notes that the state of his nose remained in a perfectly satisfactory condition.

Hamilton obviously made a huge difference to these patient’s lives, giving them back confidence and self-respect. His youngest patient was Thomas Taylor who was only 14 years old when he was operated on. Two years later, he wrote to Hamilton to inform him that he was getting on well and the mark on his forehead was fading plus his nose was much better than when he left Dublin. Within six weeks of her operation, Winifred Byrne was confident enough to stop wearing the veil she’d previously used and started to wear gold ear rings. Sometime later she visited Hamilton to show him her baby. He comments that she would have been unlikely to marry in her previously nose-less condition.

Susan Isaac, Information Services Manager