Do you Bant? The original low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) diet

12 Jan 2018

Sarah Gillam

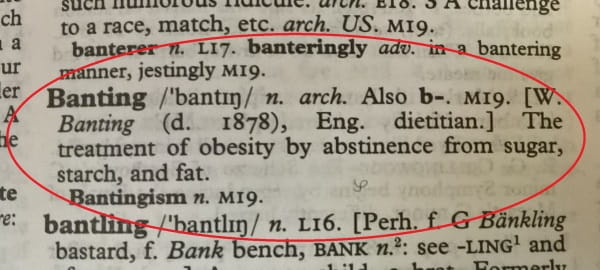

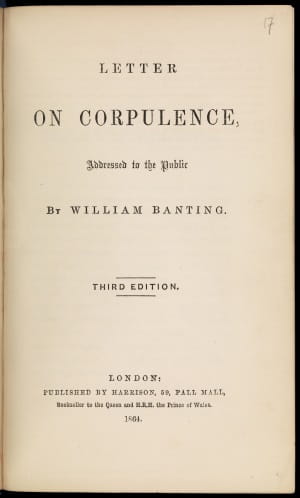

Worries about overeating and obesity seem particularly contemporary concerns, but the first popular diet book was published in London as early as 1863. In Letter on corpulence, addressed to the public, a retired undertaker, William Banting, outlined how he had lost weight by following a strict, low carbohydrate diet. His little booklet was an immediate success. The diet became the newest craze and, up until the mid-twentieth century, his name was synonymous with dieting: the verb ‘to bant’ – as in ‘to diet’ – appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary until 1963. But, although Banting popularised the diet, it was his aural surgeon, William Harvey, who devised the revolutionary eating plan.

Banting was an upper middle class funeral director whose family held the Royal warrant. He had wealth, influence and a happy family life, but, from middle age, he struggled with what he called his “parasite” – his weight. By 1862, at the age of 64 (and at just 5 ft 5” tall), he weighed 202 pounds. In his booklet, he recounts how his weight affected his life: “I could not stoop to tie my shoe…nor attend to the little offices humanity requires without considerable pain and difficulty, which only the corpulent can understand; I have been compelled to go down stairs slowly backwards, to save the jarr of increased weight upon the ankle and knee joints…”

Image to right from Wikipedia, William_Banting.png, and is in the Public Domain.

Harvey, a Guy’s-educated surgeon, had been in Paris some six years earlier, in 1856, when he had chanced upon a lecture by the eminent physiologist Claude Bernard. Bernard had outlined a new theory on the role the liver plays in diabetes. After experimenting on dogs, Bernard suggested that the liver secreted a sugar-like substance – glycogen. Inspired, Harvey began to think about the role of food in diabetes and began to research the way fats, sugars and starches affected the body.

Confronted by the obese Banting, Harvey immediately saw a connection between his bulk and his deafness. He advised Banting to give up bread, butter, milk, sugar, beer and potatoes and to live on mainly animal protein, fruit and non-starchy vegetables. For breakfast, Banting recounts he ate “…four or five ounces of beef, mutton, kidneys, broiled fish, bacon, or cold meet or any kind except pork; a large cup of tea (without milk or sugar); a little biscuit, or one ounce of dry toast”; for dinner, “…five or six ounces of any fish except salmon, any meat except pork, any vegetable except potato, one ounce of dry toast, fruit out of a pudding, any kind of poultry or game, and two or three glasses of good claret, sherry or Madeira – Champagne, Port and Beer forbidden”; tea “…Two or three ounces of fruit, a rusk or two, and a cup of tea without milk or sugar”; and supper “…Three or four ounces of meat or fish…with a glass or two of claret”. For a nightcap, “if required” he could have a tumbler of grog “or a glass or two of claret or sherry”.

Image to left from Wikimedia Commons, Letter on corpulence Wellcome L0068580.jpg, from the Wellcome Collection, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

Harvey’s name did not appear in the first two editions. Banting explained: “In the first and second editions, I thought that to give his name would appear like a puff, which I know he abhors”. But in the third edition, Banting revealed the identity of his adviser and also added a long note by Harvey, explaining the diet. In 1872, Harvey wrote his own weighty, academic book, On corpulence in relation to disease, with some remarks on diet.

But Harvey’s defence of the diet was largely unsuccessful. Despite its popularity, ‘Banting’ was always controversial, in part because, though it was effective, there was at that time no convincing scientific theory to explain how it worked. Harvey was ridiculed and, in the end, his practice began to suffer. ‘Banting’ was gradually eclipsed by low fat diets, only to be resurrected in the 1970s with another surname attached – as the Atkins diet.

Sarah Gillam, Lives of the Fellows Assistant Editor