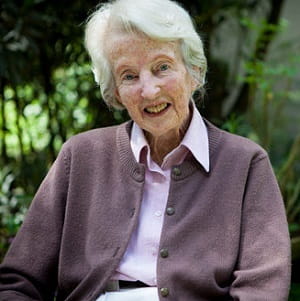

Catherine Hamlin: pioneered the treatment of obstetric fistula in Ethiopia

05 Mar 2021

Sarah Gillam

The Australian obstetrician and gynaecologist Catherine Hamlin, who died last year, spent more than 60 years in Ethiopia treating women who, because of a lack of basic obstetric care, suffered from horrific childbirth injuries or fistulae. With her husband, Reginald (Reg) Hamlin, she pioneered surgery for the condition and set up the first hospital in Africa dedicated to fistula repair. Hamlin Fistula Ethiopia continues their work, now running six hospitals, a college of midwives, a rehabilitation centre for long-term patients and a network of midwifery clinics.

Catherine was born in Sydney, Australia in 1924 and studied medicine at the University of Sydney. After qualifying and completing internships, she applied for a resident post at the renowned Crown Street Women’s Hospital, also in Sydney, where she was interviewed by the medical superintendent, Reg Hamlin. She was accepted: she and Reg fell in love, and they married in 1950.

The couple had a strong Christian faith and felt called to serve overseas. In 1958, they saw an advertisement in The Lancet for a gynaecologist to set up a school of midwifery at the Princess Tsehai Memorial Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. After some hesitation, they applied, were accepted and, with their six-year-old son, Richard, arrived in the city in 1959 to take up a three-year contract. They stayed on, devoting the rest of their lives to serving the women of Ethiopia.

Within a day or so of their arrival, one of their new colleagues, a doctor, Margaret Fitzherbert, warned them of the immensity of their task, telling them they would see obstetric complications and suffering on a huge scale. In particular, Fitzherbert told Catherine, ‘The fistula patients will break your heart.’

Obstetric fistulae happen to women who have gone through obstructive deliveries, perhaps because the baby is too big or in breech, or the woman too small and immature. If there is no midwife to help or the mother cannot get to a hospital, labour can continue for days. Eventually, the baby may be expelled, stillborn, but the pressure of labour can tear the bladder, vagina, uterus and even rectum, creating holes – fistulae. The woman is left incontinent, sometimes doubly so.

In the West, obstetric fistulae are now rarely seen, but in Ethiopia, particularly in remote, rural areas, there are few midwives to help women give birth. And women may also marry very young, becoming pregnant when their bodies are still immature. Tragically, women with fistula are often ostracised by their communities and may spend years, sometimes decades, living isolated lives.

When the Hamlins arrived in Ethiopia little could be done to help these women, who were often turned away from hospitals. Catherine and Reg decided to find out as much as possible about the repair of fistulae. They read surgical literature from the 19th century and corresponded with specialists across the world, including with the Egyptian obstetrician and gynaecologist Naguib Mahfouz, the Nuffield professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at Oxford, Chassar Moir, and with Heinrich Martius in Germany.

Eventually, the Hamlins felt able to tackle their first fistula repair. They chose a young woman with a relatively small tear to her bladder; Reg performed the operation and Catherine helped. After 14 days, the patient’s catheter was taken out; she was continent and the operation was a complete success. After 22 more operations where they worked together, with an outstanding success rate, Catherine began operating on her own.

Word spread and many more women started arriving at the hospital suffering from fistulae, often travelling for miles. One woman took seven years to get to the hospital in Addis Ababa – it had taken her that long to beg for the fare at a bus stop. At first the Hamlins opened a ten-bed clinic in the grounds of the Princess Tsehai Hospital, and then, in 1971, using money from New Zealand, they bought a piece of land on the outskirts of Addis Ababa and began planning a new hospital. On 24 May 1975, in the midst of a period of political turmoil in Ethiopia, they officially opened the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital.

Catherine and Reg prioritised teaching Ethiopian surgeons their techniques, including one ex-patient, Mamitu Gashé, who had arrived as a teenager. In 1993, Reg died, but Catherine stayed on in Ethiopia, expanding and developing the fistula service. In 2002 Desta Mender (‘Joy Village’ in Amharic), a rehabilitation and reintegration centre, was opened, a refuge for women with long-term injuries. Another five regional hospitals were opened between 2006 and 2010, and, in 2007, the Hamlin College of Midwives was finally established, offering a four-year training to students from the country’s remotest areas. The midwives now work in an extensive network of rural clinics.

The Hamlins had to become expert fundraisers, or ‘professional beggars’, to use Reg’s phrase. In 2001, Catherine’s autobiography, The hospital by the river: a story of hope, was published, telling the story of the women with fistula and the hospital. In writing the book, she said her motive was simple: ‘…to break the hearts of millionaires’. Three years later, she appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show in the United States to talk about her work. After the show, Oprah wrote her a large personal cheque and another $3 million was donated by viewers.

Catherine received many honours. She was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace prize (in 1999 and again in 2014), and in 2009 won the Right Livelihood award. In her home country, she was honoured with the Companion of the Order of Australia in 1995 and, in 2001, the Australian Centenary medal. In her adopted country, in 2019, the prime minister Abiy Ahmed, presented her with an eminent citizen award, recognising her 60 years of service to Ethiopia. She also gained fellowships from several Royal Colleges, including, in 1999, the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Catherine died on 18 March 2020 at the age of 96. She left behind a thriving organisation, Hamlin Fistula Ethiopia, which continues her work, raising funds to fulfil her dream: ‘…to eradicate obstetric fistula. Forever.’

Sarah Gillam, Lives of the Fellows Biographies Editor