“Phossy jaw” and the matchgirls: a nineteenth-century industrial disease

28 Sep 2018

Susan Isaac

In the early 19th century, it was discovered that adding yellow (now called white) phosphorous to matchstick heads made them easier to ignite. The demand for the new ‘strike-anywhere’ matches was enormous, creating a profitable international industry. It also led to a new industrial disease that lasted until roughly 1906, when the production of phosphorous matches was outlawed by the International Berne Convention.

By 1858, detailed medical reports of a disease involving the slow progression of exposed jaw bone started to appear. Phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, commonly called ‘phossy jaw’, was a really horrible disease and overwhelmingly a disease of the poor. Workers in match factories developed unbearable abscesses in their mouths, leading to facial disfigurement and sometimes fatal brain damage. In addition, the gums developed an eerie greenish white ‘glow’ in the dark.

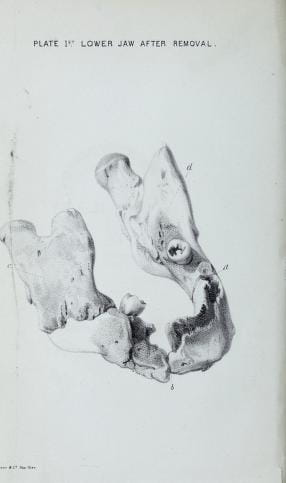

In 1857, James Rushmore Wood wrote an article about his experience of operating on a patient with ‘phossy jaw’, called ‘Removal of the entire lower jaw’ which included illustrations of the results. The first half is a detailed case history of his patient, 16 year old Cornelia. She’d worked eight hours a day in the packing department of a New York match factory for two and half years. In May 1855, she was seized with toothache and swelling on the right side of her lower jaw. To relieve the pain, first her gums were lanced and later a tooth was extracted, but the swelling gradually increased until a spontaneous opening formed under her jaw which continuously discharged pus. Despite this, she continued to work in the factory until a week before she was admitted to Bellevue Hospital on 17th December 1855.

When she was admitted, her general health and appetite were described as good but it was difficult and painful for her to chew. Her jaw hurt, her face was swollen and the bone of her lower jaw was damaged. After investigation, Wood decided to operate and remove the dead bone on the right side of Cornelia’s jaw on 19th January 1856. No anaesthetic was used. As the operation progressed, Wood used a chain saw (a piece of equipment that looks more like a cheese wire) to divide the bone; unfortunately the chain broke and he had to use forceps to remove the entire right side of her lower jaw.

By the 26th of January the wound had healed, but the left side of her jaw was diseased and discharging pus, so a second operation was carried out on 16th February to remove the remaining part of Cornelia’s lower jaw. She was given twenty drops of laudanum to produce sleep; a few days later four ounces of wine were ordered “to be given during the day along with a daily lead and opium wash”. On the 23rd February the swelling had subsided and the contour of her face is described as perfect but importantly, the movement of her tongue and mouth had been retained. The patient recovered well and Wood was particular proud of the appearance of this patient after the operation. He describes an operation that nowadays would be carried out by a specialist Maxillo-Facial Surgeon with considerably more equipment antibiotics than he had available, as well as more recent developments such as antibiotics.

The second half of the tract is an overview of the existing international knowledge about the disease, citing French, English and German writing. He outlines the general course of the disease and treatments before finishing with eight shorter case histories. All the victims are in their 20s and some had worked in the industry since childhood. The international spread of the disease is reflected in the RCS collection of tracts and pamphlets, which contains items on the subject from England, France, Germany and the United States.

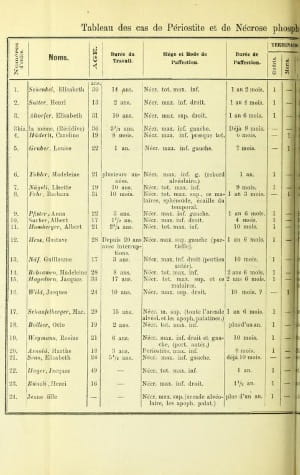

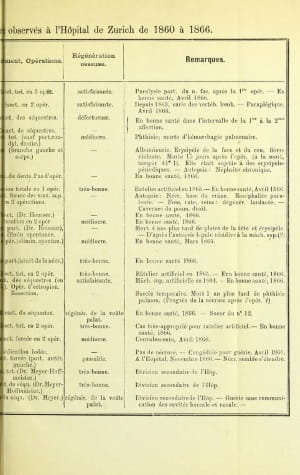

These tables, taken from De la périostite et de la nécrose phosphorique by Haltenhoff in 1866, give the ages, duration of time worked in the factories and the duration of the illness of the victims. Haltenhoff had made a close study of Telat’s 1857 work, De la nécrose causée par le phosphore : thèse de concours pour l'agrégation, section de chirurgie. Both contain case studies and autopsy reports.

In England, Charles Dickens wrote about ‘phossy jaw’ in Household Words as early as 1852, while Annie Besant organised the London matchgirls’ strike in 1888, protesting against the use of phosphorus in the manufacturing process. The disease could be prevented by using the safer but more expensive red phosphorous and following good occupational hygiene. William Booth, Salvation Army founder, opened a factory to sell boxes of matches advertised as “Lights in Darkest England”, applying moral pressure to his competitors. European countries started to ban the use of white phosphorous from 1872, but there wasn’t a total ban until 1910.

21,496 items from the Library’s 19th Century Tracts and Pamphlets Collection were digitised between 2015-2016 as part of the UK Medical Heritage Library (UKMHL) project. This made the majority of the collection freely accessible online to everyone. The entire collection will soon be available on SurgiCat+, the Library catalogue, to make them even easier to find.

Susan Isaac, Information Services Manager