Surgeons during the COVID-19 peak: the experience of an ICU support team

18 Aug 2020

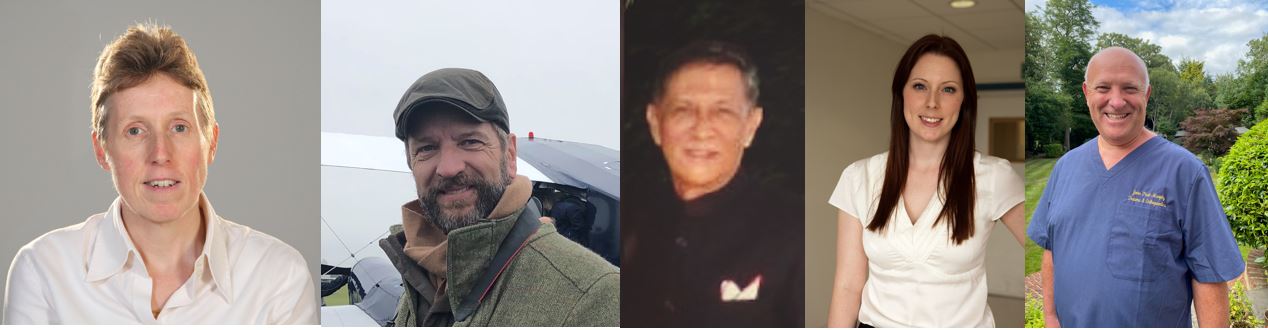

Sue Clark, Matthew Bartlett, Deepak Batura, Abul Habib, Ian Holloway, Laura Muirhead, John Murphy and Robert Reichert

In this blog series, Professor Sue Clark, a consultant colorectal surgeon at St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow, and her colleagues Matthew Bartlett, Deepak Batura, Abul Habib, Ian Holloway, Laura Muirhead, John Murphy, and Robert Reichert, all based at London North West University Hospitals NHS Trust, discuss setting up a team of surgical consultants to support the intensive care unit during the peak of COVID-19.

COVID-19 hit Northwick Park Hospital hard and early. On 3 March 2020, the first COVID-positive patient was admitted; on 9 March elective surgery stopped; by 16 March the intensive care unit (ICU) was full and patients were being ventilated in the operating theatres; on 19 March a critical incident was declared. A 22 bedded intensive care unit, split across two areas, was expanded to a capacity of 60 beds. The spaces occupied changed several times, as it became clear that using multiple small rooms was unworkable, with staff stretched beyond any reasonable expectation by this tripling in capacity, coupled with a sickness rate as high as 40%. Nurses, healthcare assistants and junior doctors were redeployed to the ICU, as were all senior anaesthetists. It rapidly became clear that there were many practical and logistical challenges, but that there was simply not enough consultant anaesthetist capacity to deal with them.

A team of eight surgeons, the ‘surgical support consultants’ (SSC), was formed to directly assist the team in intensive care. This group knew their way around a confusing hospital campus, had the right teamworking and communication skills and sufficient clinical nous to take on several tasks and to spot trouble. We worked the same 12-hour shifts as our anaesthetic colleagues, with one team member on at night and two during the day.

The first task of each shift was coordinating handover. We developed an agenda, which covered allocation of the anaesthetic consultants to different roles (covering the various ICU areas, intubation and proning teams), updates on the bed state and potential transfers, as well as the introduction of new processes as they evolved. We recorded and disseminated the information by writing the bed state and personnel allocations on a whiteboard, photographing it and posting the photograph on the ICU WhatsApp group. Walkie talkies also became an essential mode of communication, as using mobiles while wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE) is impossible.

A very major problem early on was the difficulty in tracking referrals and admissions to ICU, previously done entirely on paper. On 27 March, it was agreed that an existing piece of software used to manage acute orthopaedic admissions should be modified; an initial version was installed on 30 March, and tested and modified by the SSC team during that week. It went live the following week. This system allowed all referrals to the ICU team to be logged, the outcome of assessment recorded and a list of patients for review to be maintained and updated. It allowed the bed state to be viewed in real time from any hospital computer, as well as providing information on ventilation status and the requirement for renal replacement.

An ICU which usually cares for around 800 patients per year, had 257 admissions with COVID-19 over six weeks, with at times 6-10 intubations per 24 hours. The only way to cope with this unrelenting inflow was to transfer patients out to other hospitals in the North West London sector and elsewhere. Overall, we transferred 133 patients out (19 to the London Nightingale Hospital, comprising over half of the total admissions to that unit, including the first patient to arrive there, who reportedly spent his first night as its sole occupant).

The first step was working with the clinical team in each area to identify patients suitable for transfer. Each morning there was a telephone call with the ICU network coordinator to share information on these patients and potential bed availability. The next step was to coordinate a telephone conversation between the intensivist caring for a particular patient in our unit and the consultant at the hospital that might take them. In normal times, a straightforward matter, but a challenge with doctors at both ends in and out of PPE. Some receiving hospitals sent retrieval teams, but the network also put together teams comprising two anaesthetists and an ambulance that met up at our site – requiring help with car and motorbike parking, changing into scrubs and then PPE; a cup of tea and a comfort break were warmly welcomed. Transfer teams needed to get to the right ICU site, through the right entrance, and to the right patient, and then back out again to the ambulance bay, usually with input from security to clear a path and reduce infection risk. Some then returned with contaminated equipment and to retrieve their belongings from an unfamiliar hospital within which they had no access. The importance of these transferred patients cannot be overstated; each day was a battle for the SSCs to transfer enough patients out of the ICU during daylight hours to make room for the six to ten who would arrive over the subsequent 24 hours. We regularly started the day with only one or two available beds but never found ourselves without capacity overnight, transferring up to eight patients in a single working day to make room.

It became clear early on that patients with respiratory failure due to COVID-19 responded well to being positioned prone, again a major logistical challenge. Firstly, one of us worked effectively full time recruiting and then coordinating a proning team to cover all shifts, with between five and eight people (mostly dentists and physiotherapists) on each shift. The team members also assisted the thinly stretched nursing staff with turning patients and dental hygiene. Working over two separate areas (separated by three floors and several hundred metres), attending to new requests for proning and then deproning patients 12-16 hours later became chaotic, so the patient tracking software was modified to allow ‘proning referrals’ and to automate the scheduling of subsequent deproning.

We responded to a range of requests, such as obtaining items of PPE when needed, sourcing consumables from other hospitals, relocating ventilators and haemofiltration machines, finding operating department practitioners to service ventilators requiring urgent attention, tracking down a range of other personnel required quickly, and coordinating the relocation of ventilated patients around the hospital in response to the ever-changing bed state.

Our work pattern included ‘zero days’ and reserve shifts to cover sickness. Of the original eight team members, two developed COVID-19 infection, and had the peak continued longer, a larger team would have been needed. As it was, we supplemented the team just as we were no longer required. However, all new members experienced at least one shift, and we are ready to mobilise again if required. A shared drive on the hospital IT system was set up for us, along with a group email account. These are still in place. The essential equipment we assembled (two mobile phones and chargers, a lift override key, and universal access cards) and procedure and process documents we created, are also safely stored.

We were busy, and undoubtedly freed up our anaesthetic colleagues to provide direct care, rather than spending frustrating hours on the telephone or tackling some of the tasks themselves. Undertaking this role was a humbling experience and we are grateful for having had the opportunity to contribute in this way. There clearly is a role for surgeons in the ICU!

'A team of eight surgeons, the ‘surgical support consultants’ (SSC), was formed to directly assist the team in intensive care.'

From left to right: Professor Sue Clark, Matthew Bartlett, Deepak Batura, Laura Muirhead, John Murphy.

This blog is from our series COVID-19: views from the NHS frontline. If you would like to write a blog for us, please contact content@rcseng.ac.uk.