Memories from the on-call room: being a surgical registrar during the COVID-19 crisis

10 Jun 2020

Natasha Jiwa

Natasha Jiwa is a trainee surgeon in General Surgery at Imperial College Healthcare Trust. In the midst of the pandemic, she was redeployed while undertaking her PhD as a Clinical Research Fellow at Imperial College London. In this blog series, Natasha reflects on the wide-ranging changes in the medical community that are the result of COVID-19.

Over the past few months, the medical fraternity has been in a state of upheaval. This was uniform across all specialties. As I sit in my on-call room (lucky to still have one), here are some reflections of how things changed during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Decision-making

Decision-making on the acute surgical take changed overnight. We saw sicker patients presenting with a deterioration in their chronically managed diseases and urgent cancers presenting as emergencies. Perforated strictures, blocked stents and everything in between. Even the decision to admit was multi-faceted. A first-time lactating mother who is febrile and tachycardic with mastitis and a C-reactive protein level of 250: I would usually request a bed without a second thought, for fluids, IV antibiotics and rest, ready for their ultrasound in the morning. However, the threshold for admission was much higher: surely they were safer at home? Do I risk them become infected with COVID-19 from either myself or the hospital?

The approach to the management of acute surgical conditions also pivoted. COVID ward rounds consisted of the consultant +/- a scribe, usually with only half their body in the room! Young, fit patients with right iliac fossa pain were being sent home with a trial of oral antibiotics and the warning of ‘a 30% chance you may re-present within the year with the same symptoms.’ We travelled back in a time machine to the era of open surgery. Patients spent longer in hospital due to larger incisions, COVID-associated ileus, and respiratory complications.

Telephone clinics

A new addition to the surgical rota included the telephone clinic. The process of calling patient after patient to tell them their investigations have been delayed or cancelled was heartbreaking, and may have aged me more in one session than the last year in clinical practice. That being said, most responded well and those in need – for example a gentleman with a locally advanced low rectal cancer who was worried that he had worsening symptoms of ‘haemorrhoids’ – are being easily identified for face-to-face clinical assessment. My concern remains how we will ever overcome the growing waiting lists accumulated from this pandemic, and many more people will suffer a poorer outcome from a treatable condition due to unavoidable delays in their care.

Training

Cessation of all elective cancer work during this time caused a prompt disruption to training. Those hit hardest appear to be those placed at either end of their specialist training, with many of the surgical trainees being redeployed to help on intensive care units.

At the other end, many senior trainees had concerns over whether they would be able to gain their CCT or undergo specialist fellowships, both in the United Kingdom and abroad. Fellowship exams are postponed until the end of the year, which is likely to impact next year’s fellowship application numbers. As a cohort, we understand that these changes are necessary. However, due to the intricate and arduous nature of surgical training, family planning, house moves and childcare must also be carefully adjusted in order to progress.

One thing which I hope will change is that foundation programmes will contain a mandatory four-month critical care placement. This will help us if there are any future peaks or pandemics and is also very useful for budding surgeons to understand what we put our patients through when we do high-risk cases.

Concerns over burnout

Burnout in surgery is spoken about most commonly behind closed doors. My feeling is that everyone feels it, but surgeons rarely talk about it. We are, more than ever during this pandemic, likely to suffer from emotional exhaustion and acute-on-chronic occupational stress. The lethal combination of a lack of training opportunities, redeployment, and recommencing administrative jobs we haven’t embarked on regularly since we were foundation year doctors means that we are likely, more than ever, to suffer from a low sense of personal accomplishment, while ironically working harder than many of us may have in our careers to date. This is precariously balanced by the care and admiration we are feeling from the country, be it gaining entry into a supermarket without having to queue or the heart-warming clap for carers (which makes us feel exceptionally emotional). We should look closely and learn from our anaesthesia colleagues who appear especially more advanced than us in recognising and managing burnout, where it does not appear to have the same stigma as in surgery.

Drive

One thing I cannot emphasise enough is that despite the struggle of the past few months, I love my job and I am proud to be a member of the medical community. We have stepped up to the mark like we do every day and every bank holiday all year, every year. I know we are all fighting our individual daily battles: whether it be self-isolation from our families when we become symptomatic so they can stay safe, or just the anxiety that we’ve forgotten how to operate laparoscopically. And yet, we are all in this together and we will do whatever it takes; I will never forget those who became a member of the proning team (shout-out to my orthopaedic and neurosurgical colleagues) or part of the 24-hour IV lines service (I always knew that vascular placement would come in handy one day).

As an important aside, I have always respected my anaesthesia colleagues, who we work so closely with and with whom we share a codependent relationship. They may begrudge us for joking with them that they are only good for adjusting our light while they complete their daily Times crossword. However, over the past few months, seeing their dedication – putting their lives on the line when intubating patients, while using their encyclopaedic knowledge to look after critically ill patients on the intensive treatment unit – it has reminded me just how lucky we are to have anaesthesia doctors with us in theatre. Particularly in an era where anaesthesia nurses are the norm in so many other countries.

If truth be told, the aftermath of this pandemic scares me just as much as the pandemic itself. I can’t help but think that all my exhausted colleagues trying to play catch up on the thousands of delayed investigations and operations may just be the straw that breaks the NHS’s back. The prompt and evidence-based guidance on the recovery of surgical services will be essential to ensuring we are not overcome by the upcoming pressures placed on us.

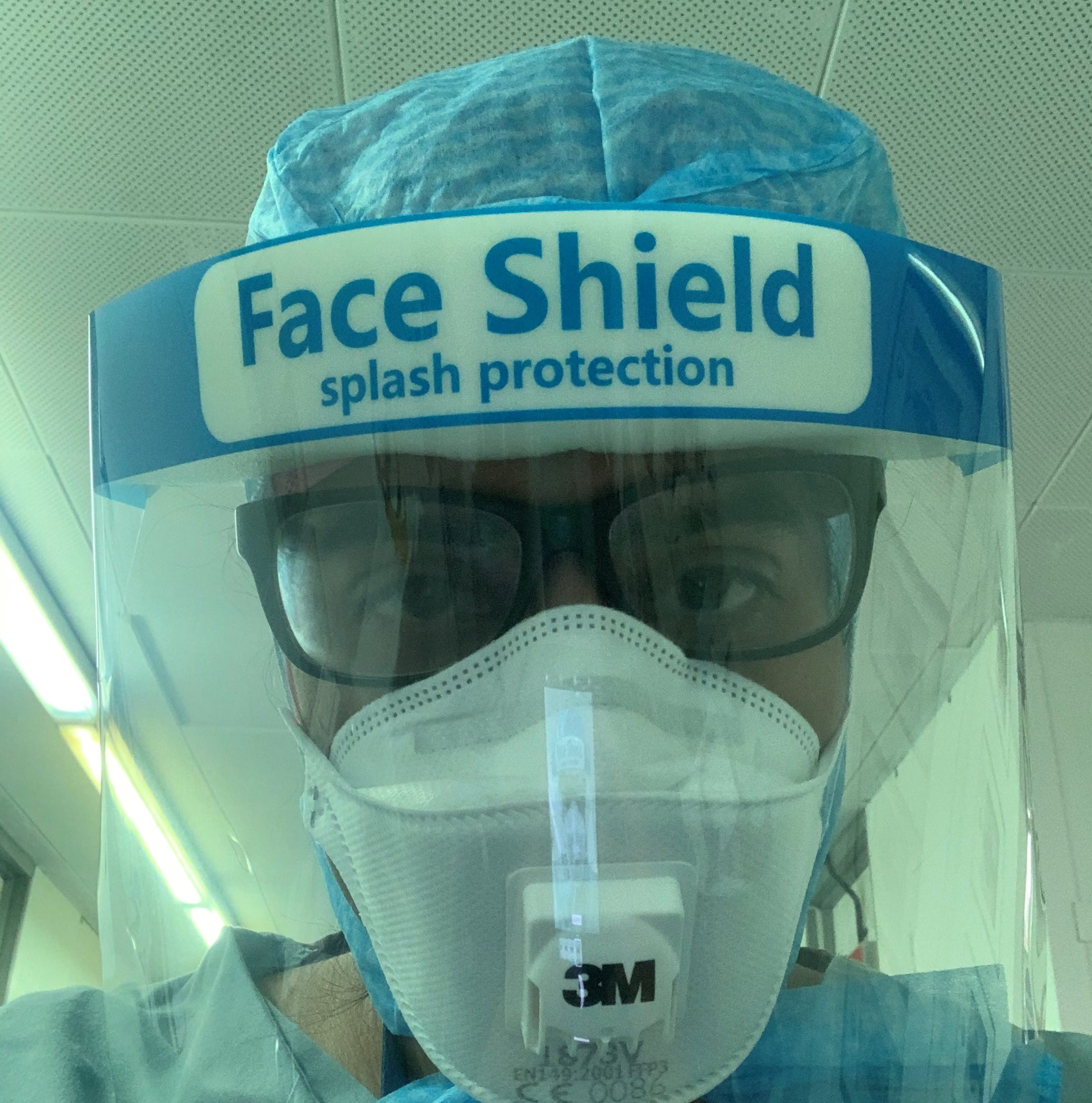

Author, Natasha Jiwa, in personal protective equipment.

'I love my job and I am proud to be a member of the medical community.'

This blog is from our series COVID-19: views from the NHS frontline. If you would like to write a blog for us, please contact content@rcseng.ac.uk.