Could you be an expert witness?

20 Nov 2019

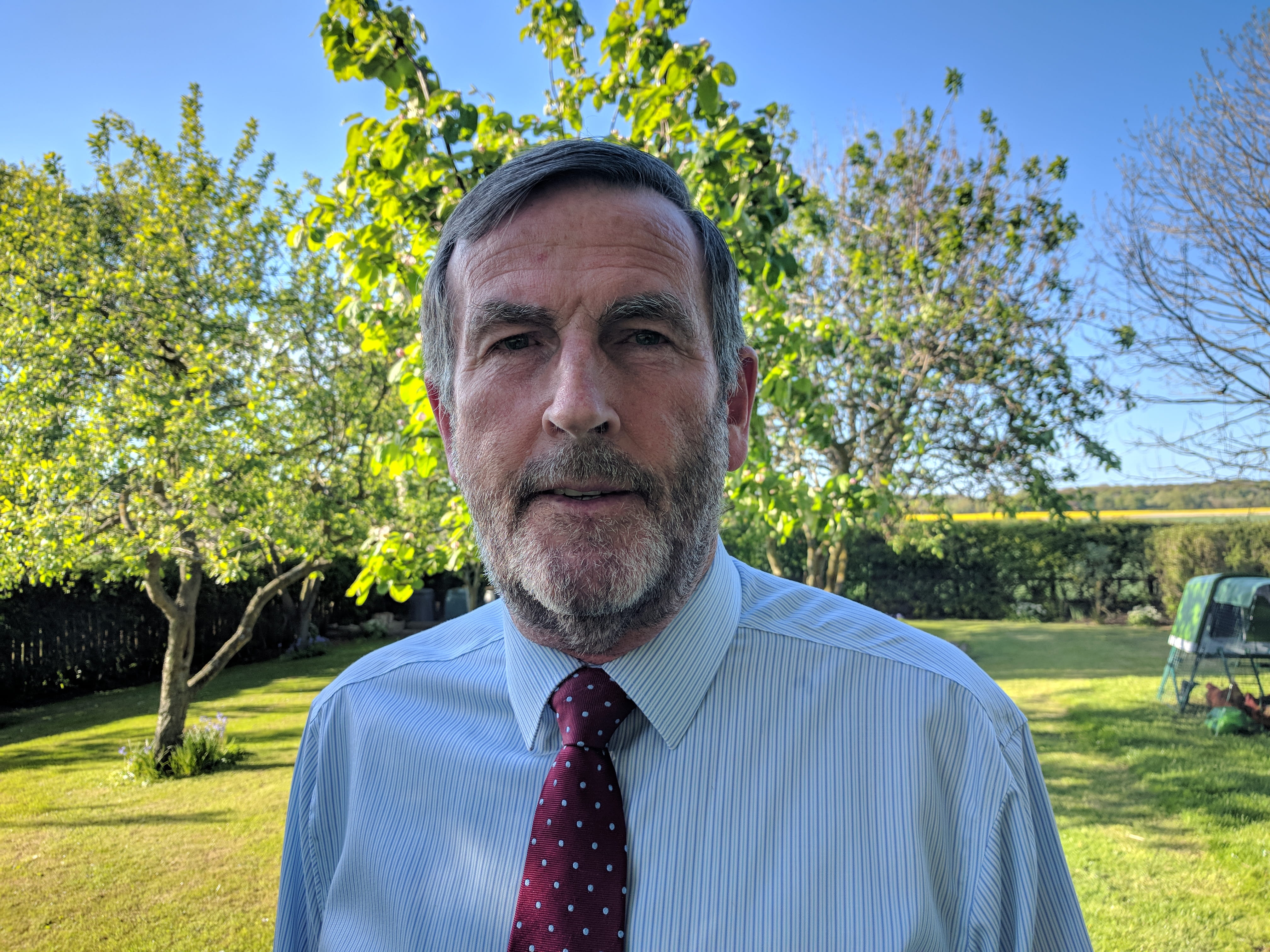

Leslie Hamilton

Mr Leslie Hamilton LLM FRCSEng FRCSEd(C-Th) is a retired Consultant Cardiac Surgeon, former RCS Council Member and he was chair of the General Medical Council’s Independent review of gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicide (published 6 June 2019). Mr Hamilton has been involved in the development of some of the key Standards documents of the College, such as Good Surgical Practice, Consent, and Duty of Candour.

When the legal system is asked to address cases involving clinical practice, it cannot function without doctors being prepared to explain the medical issues to the court. So, a doctor acting as an expert witness is an absolutely essential part of the process. There is a misconception that such “experts” have to be experts at giving evidence, or indeed “experts” in their field. Yet the legal test in the civil court is the Bolam standard: what a reasonable (not expert) doctor would have done. Indeed, the judge in the Bolam case went onto explain: “The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest skill." [1]

Both the review by Professor Sir Norman Williams [2] (set up by the then Secretary of State Jeremy Hunt following the successful appeal by the General Medical Council in the Bawa-Garba case) and the Independent Review (commissioned by the GMC at the same time), highlighted the need for more “normal” doctors to be prepared to undertake medico-legal expert witness work. So, this new guidance from the Royal College of Surgeons, as part of a series of guides on professional practice, is timely. For those new to medico-legal work, it is a valuable introduction. For those with some experience, it is a helpful opportunity to review their practice against the standards set out in the guide.

It almost goes without saying (and it is rightly stressed in the RCS’s guide) that any surgeon thinking about starting medico-legal work should attend one of the many courses available on the role of the expert, and preparation of a report, as set out in Part 35 of the Civil Procedure Rules [3]. On the very rare occasions that a surgeon is asked to give an opinion in a criminal investigation, they should be given very clear instructions on the law by their instructing solicitor and refresh their memory on the revised comprehensive guidance on GNM published this year by the CPS (Crown Prosecution Service). [4]

During our Review, we heard much disquiet about the role and function of medical experts – we devoted 4 of the 29 recommendations to this issue. However, while we were focussing on all the courts which are “high stakes” for doctors (Coroner, General Medical Council and criminal), the RCS’s guidance gives a broad understanding of the system, with most of the emphasis rightly on the civil court (where doctors are sued for negligence). In 2018/19, NHS Resolution [5] received 10,678 new clinical negligence claims compared to an average of 16 police investigations per year in England and Wales for gross negligence manslaughter (GNM).

Any doctor beginning their medico-legal experience will most likely do so by providing a “breach of duty and causation” report in a clinical negligence case in the civil court. Therefore, while the RCS suggests that surgeons may provide reports up to 3 years after retirement (with which I agree), both Williams and our Review said that the doctor giving an expert opinion in a criminal case must have been in active and relevant clinical practice at the time of the incident, as the outcome of a criminal case (imprisonment) is of a different magnitude than the financial compensation in a civil case.

If you were unable to attend the RCS’s excellent meeting “Surgery and the Law” (14 November in Newcastle), you can at least familiarise yourself with this guidance, before considering whether to undertake work as a medical expert witness.

Find out more about the RCS’s new guidance: The Surgeon as an Expert Witness

[3] https://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules/part35

[4] https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/gross-negligence-manslaughter

[5] https://resolution.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/NHS-Resolution-Annual-Report-2018-19.pdf