Vinod Patel: Long-term outcomes associated with a short-term surgical mission managing complex head and neck facial disfigurement

Background

The health status of Ethiopia is poor, even when related to other low-income countries including those in sub-Saharan Africa.(1) The common health problems in Ethiopia have their roots as manifested in the complex poverty syndrome of malnutrition. According to the 1993 survey of Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute (EHNRI), the prevalence of under-weight children and stunting stood at 47 % and 64%, respectively, among children between the ages of 6 and 59 months (MEDaC, 1999/00).(2)

Noma (cancrum oris)

The issue of malnutrition is complex but highly important in the Sub-Saharan region due to its critical role in the condition noma (cancrum oris). Noma is commonly described as a facial gangrene and affects young children between the ages of 2 and 6 years suffering from malnutrition, living in extreme poverty and with weakened immune systems.

Noma starts as infection intra-orally often as a sore on the gingivae before progressing to ulcerative necrotising gingivitis. The progression of this leads to a facial infection and cellulitis spreading through soft and hard tissues of the face and mouth. The spreading infection then leads to necrosis of the soft tissue leading to the loss of the lips, cheeks and gingiva. Depending on the severity and spread it can lead to loss of vision and trismus. The subsequent outcome can leave the patient with a poor aesthetic appearance and a lack of basic functions such as eating, drinking, breathing and speech. In the acute phase of noma, without treatment the infection carries a 90% mortality rate.

Benign tumours

Access to healthcare in Ethiopia may be limited due lack of finances, distance of travel, poor and unsafe conditions to travel or stigma and discrimination leading to social isolation. In such cases, benign tumours have the opportunity to expand and enlarge, producing significant deformity and disability. Approximately 28% of the global burden of disease is amenable to surgical intervention, a proportion that is higher in the developing world.(3) In Low & Middle Income Countries (LMICs), much of this burden is borne by a rapidly growing international charitable sector, in fragmented platforms ranging from shortterm trips to specialized hospitals.(4)

Short-term surgical missions

One avenue included short term surgical missions (STSMs) where the charity sends surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and/or supporting staff - along with, at times, surgical instrumentation and technology - into LMIC hospitals and clinics for short periods. Often, these NGOs perform a restricted set of surgeries, relying on local physicians for follow up.(4) It remains important to determine the long-term outcomes of surgery to avoid recurring errors as well as evaluation of the benefit of surgery too. It is well documented that there are increased complication rates with cleft surgery(5) and increased mortality with hernia surgery(6) compared to high-income countries. The truth is that the impact of STSMs is largely unknown. The follow-up of patients is often deemed too difficult, not a priority and often seen as an unnecessary additional cost - hence the outcomes remain unknown.

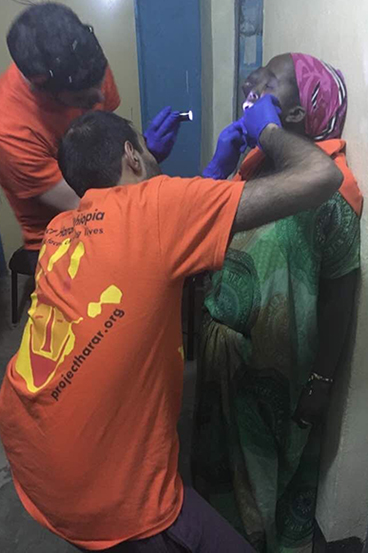

Figure 1 shows a review consult for a noma patient with the presence of a local governmental official providing translation. It can be noted that this patient still chooses to cover up following her facial surgery.

Objects and methodology

Project Harar (PH) is a charity treating head, neck and oro-facial disfigurement in poor and rurally isolated people from across Ethiopia. Annually the charity runs a ‘complex mission’ whereby 25 international volunteers surgically manage the most severe, complex and challenging facial disfigurement cases. To date, 6 complex missions have treated approximately 300 patients. The mission provides education and surgical training to the Ethiopian registrars to manage future generations. I have volunteered for 3 consecutive complex missions; leading the pre-operative phase and have provided, assisted and taught in the operative phase.

A shortcoming of the surgical missions is the lack of long-term patient follow-up (LTFU). There are legitimate reasons for this, however, without this information it remains impossible to deem surgical procedures successful. It is necessary to have LTFU post complex surgery in the developed world and these principles should be no different for Ethiopia. Only with LTFU can we determine whether surgery provided should be sustained, amended or discontinued. This will inform best practice for the future and is crucial not just to the patients but also for the charity in ensuring best use of resources into the future.

The primary objective was to determine the long-term success and outcome of the surgical procedures provided through the 6 complex missions.

• This is best determined through post-surgery history, semi-structured interview, examination +/- any relevant imaging

The secondary objective was to establish the consequence of the intervention on the patient physical, social and mental health.

Patients were identified and contacted by the PH outreach workers and transport organized to their nearest health centre hub in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Harar and Hawassa. I visited these hubs over a period of 2 weeks with the PH Programs Manager and an official translator. Medical examinations, interviews, questionnaires and photos were undertaken with patient consent.

Upon return, data and semi-structured interviews have been categorized into themes for analysis. Longterm review was fundamental to determining success. Providing this evidence would support the charity to increase and improve its complex mission efforts meaning more free surgery and subsequently more training and education for Ethiopian surgeons. Finally any patients identified as having problems following surgery would be identified and linked to further treatment promptly.

Activity

The review mission commenced on 16/02/17 until the 02/03/17. Three major regions were visited (Addis Ababa, Oromia and SNNPR). Within these districts we travelled to numerous villages. All patients were seen following approval form local government officials. The officials also joined us for the review clinics as there were direct links to the patient as their team had identified and communicated with the patients. This allowed for improvement in relationships and communications between NGOs and government.

Reviews took place in either a local hospital or treatment centre. The medical team maintained the highest standards of infection control, confidentiality and dignity for all patients. Each patient was reviewed with his or her previous PH information identified where possible. Official government and PH translators were used to conduct a full clinical consult. Verbal consent was gained to examine patients and written consent for clinical photography (Figures 1-4 below). All patients were asked an additional standard 6 questions at the end of the review consult with fixed options for answers:

- Did you feel you were given adequate and appropriate information to provide consent? – Yes, No, N/A

- Were your expectations met? – Met, Below, Above

- Following your surgery how has your quality of life been? – Improved, No change, Worse

- Following your surgery how has your function been? – Improved, No change, Worse

- Following your surgery how would you judge your appearance? – Improve, No change, Worse

- Knowing what you do about your surgery would you still have it done again? – Yes, No

There was a particular focus on the impact of surgery on function and social history (martial status, jobs, education and social interaction) as the charity is aware of the social stigma surrounding facial disfigurement. A select group of patients were invited to participate if they wish to do in the DISC-12 (amended) questionnaire. This questionnaire is internationally recognized and translated regarding stigma and discrimination in mental health. The questionnaire is ideal and holds many appropriate concepts and questions relevant to patients with facial disfigurement. With the help of Kings College London and Addis Ababa University who are currently using this in Ethiopia we gained permission for its use in a feasibility setting to determine if there is good standing to amend it officially for it to be used as an appropriate tool in STSM.

Figure 2 shows a review consult for a young boy with a facial vascular malformation that continues to enlarge

Figure 3 shows a review consult taking place outdoors for a patient who had a large parotid mass which has healed well and shofdgfdgdws no signs of recurrence.

Figure 4 shows review examination for a patient with complex facial neurofibromatosis. The consult was taking place in the evening with lack of light.

Conclusion and future actions

Conclusion

The review mission saw a total of 83 patients across the 3 districts of Ethiopia. The data obtained (quantitative and qualitative) from the mission is in the process of being organized and will then be analysed. In general, the surgery delivered by PH had provided a positive impact on patients on their appearance, function and quality of life. There were numerous heart warming stories of patients getting married, obtaining jobs, attending school and even having processions in the street to welcome back a ‘cured’ patient. The review mission also highlighted where patients has suffered complications and we were therefore able to action referrals or treatment requests for patients where appropriate.

This mission highlights the difficulty and complexity of reviewing STSM patients who are in remote areas. The logistics are complex however this information obtained has been invaluable. It has reassured the charity and the health professionals that the treatment being offered is providing a positive impact for patients.

Future actions

Two areas have been identified as areas to extend our current work.

Until recently the only achievable approach to reviewing patients was to either ask them all to return to a central point to be seen by the medical team which comes with a huge expense and loss of earning for the patients or alternatively, for a medical team to visit the patient closer to home. The latter is time consuming and at times unsafe. Furthermore some areas remain inaccessible via standard transport. However, with improved technology and communication via smartphones some of these issues maybe achievable easily and at low cost.

In one case that the medical team were keen to review, the patient was unable to attend and we were unable to travel a further 1000km to review him. The local officer in charge of the district within one hour of our request to see him was able to speak to him on the phone and provide a telephone review. Following this a photo of the patient was also available via a smartphone. This example could be extrapolated to formulate a protocol to allow for review patterns to occur and based on this to identify those patients who either report issues or complications and a focus to ask these patients to re-attend.

Currently the charity has a substantial presence in the 3 districts we visited – Addis Ababa, Oromia and SNNPR. The latter 2 districts are vast and even within this area our coverage is limited (Fig. 5 below). In context to the whole country, we have no established links or reliable contacts to provide patients in very rural aspects of the North and West of Ethiopia. The model achieved in the South and East has worked well with involvement and agreement with governmental officials as well as NGOs and missionary establishments. This process requires replicating in the North and West as it is likely that the rural nature of these areas and lack of healthcare access and poverty will mean there will also be patients in these regions with large facial deformity. This will essentially require a scoping mission.

Figure 5 shows the two (circled) predominant areas PH has worked to identify patients with facial disfigurement. The circle highest up on the East side was an area we travelled to numerous villages. It highlights the vast areas of Ethiopia that we have not been able intervene yet.